The Jollof Chronicle: A Remarkable West African Rice Dish

Dive into everything you (n)ever needed to know about Jollof Rice. Explore the origins of the dish and discover its diverse preparations across West Africa.

The Experience

At its core, Jollof is a rice dish cooked in a rich and aromatic tomato-based sauce. Sounds simple right? Not so fast.

Every country in West Africa has their own style of making it, every family has their own take on that style, and everyone thinks theirs is the best. The process is a labour of love, and the end result reflects it. A bad Jollof leaves you questioning why you put in so much effort when you could have just had plain rice. It’s a quiet and shameful meal. In my experience, the easiest way to ruin Jollof is either by not cooking the tomato and pepper blend long enough or by adding too much water was which causes the rice to turn mushy.

But when you cook your Jollof right… oh my is it something special. The first thing that hits you is that signature smoky aroma, and as it does so you feel your stomach start to rumble. Then you look at that beautiful, sunset-stained rice and go in for your initial bite. It’s an explosion of flavour inside your mouth as you feel that perfect combination of deeply stewed onions, peppers, tomatoes and other aromatics work their magic. My brain always blacks out after that part. All I remember afterwards is confusingly staring at an empty plate wondering where my food went. I suspect the dog has been spiking my drinks and eating it for himself.

Nevertheless, I am getting off track here. The purpose of this post was not to discuss how delicious Jollof rice is (to find that out for yourself, try the Nigerian version here: https://ourkosherkitchen.com/recipe/nigerian-jollof-rice/), but instead uncover where Jollof rice comes from and its many methods of preparation across West Africa.

Jollof’s Ancestor

Jollof rice is actually derived from another dish named ‘Thiéboudienne’ (also spelt ‘Thiébou djenne’ and ‘Ceebu Jën’; pronounced “chee-boo-jen”), which translates to ‘rice with fish’ in Wolof. Thiéboudienne is Senegal’s national dish and is inscribed on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

What is Thiéboudienne?

Like Jollof, Thiéboudienne is also cooked in a flavourful stew. However, that is where the similarities end. As suggested by its name. Thiéboudienne includes seafood. Typically used is a firm white fish, such as grouper or snapper. These are often stuffed with a parsley-based mixture called ‘rof’ by slicing shallow slits into the fish.

Moreover, whatever vegetables may be found fresh at local markets are also incorporated. Examples include onions, parsley, garlic, chili pepper, tomatoes, carrots, eggplant, white cabbage, cassava, sweet potato, okra and bay leaf. Tomato is common, but not an absolute requirement. Most notably, Thiéboudienne uses broken rice. This is because while Senegal was under French colonial rule, large quantities of rice would be imported from French Indochina. France received the highest quality rice, while the leftover rice debris was sent to Senegal. This broken rice soon replaced local food crops and soon became a staple of Senegalese cuisine.

Thiéboudienne is conventionally presented in a shared dish. A layer of rice forms the base with fish positioned at its centre, encircled by hearty vegetables. Commonly served alongside Thiéboudienne is a fresh tamarind that has been peeled and soaked in the cooking sauce, as well as some of the crispy rice that was stuck to the bottom of the pot (similar to socarrat in paella). Fresh lemon wedges and parsley generally garnish the dish.

Origin of Thiéboudienne

Oral stories recall the birth of Thiéboudienne as having occured on the island of Saint-Louis, Senegal as an invention by one of the colonial governor’s private chefs, Penda Mbaye. Although she typically cooked the dish using barley, a shortage once compelled her to substitute broken rice. This version then proceeded to rapidly grow in popularity throughout Senegal until it spread across all of West Africa.

Mbaye lived from 1904-1984, and French colonial rule in Senegal lasted until 1960. Assuming that Mbaye must have been at least 18 years of age to work as a cook, that means Thiéboudienne was created sometime between 1922-1960. Therefore, according to this account, Jollof rice as we know it today would have either originated during the same time period or sometime after.

Spread

Food historian James McCann reasons that Jollof likely travelled across West Africa through patterns of communication that was initially established during the reign of the Mali Empire and persisted after its collapse. The Djula people played the most vital role in that cultural dispersion.

“Found in almost all West African commercial centres, were a trade diaspora who established cultural enclaves in areas as widely dispersed as the variations of Jollof rice itself… Jollof rice also appears to have diffused as part of a regional cultural and economic diaspora that soon manifested itself in local cooking cultures”.

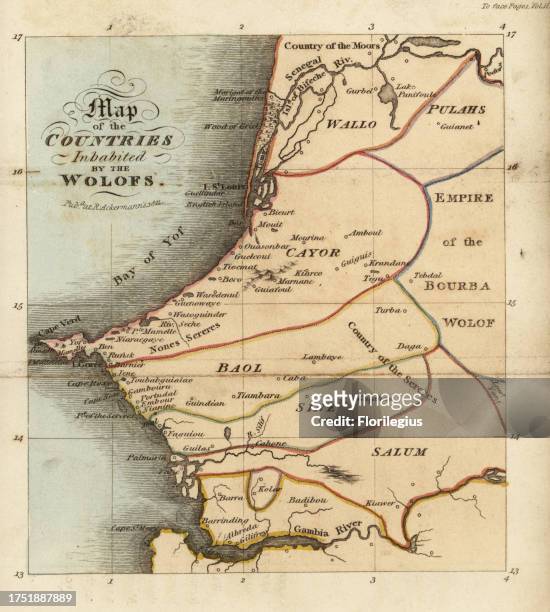

The Wolof Empire

Jollof rice likely acquired its name as a means of honoring the inventors of Thiéboudienne, the Wolof people, descendants of the former Wolof Empire (also spelled ‘Wollof’, ‘Jolof’, ‘Djolof’’; pronounced “Jollof”). Ellie from The Past is a Foreign Pantry notes that the history of Wolofs “probably dates to around the 12th century when people migrated west following the collapse of the Empire of Ghana”. The Wolof Empire covered parts of today’s Senegal and The Gambia, as well as the southwestern coast of Mauritania. Additionally, its positioning on the Senegal river enabled travel further inland, thus increasing opportunities for trade.

The Wolof Empire was in power from 1350 until 1549, when its vassal states declared independence. Subsequently, the Empire transitioned into a Kingdom. Later in 1854, the French began their conquest of the Kingdom of Waalo (the northernmost former vassal state). By 1890, they had conquered the whole of Senegal, and the Wolof Kingdom was no more.

Still, its legacy lives on. Wolofs are the largest ethnic group in Senegal, comprising about 40% of its people. Additionally, they make up 8% of the population in Mauritania and 16% of the population in the Gambia (in the capital city of Banjul they are the majority).

Variations

As Jollof spread across West Africa, local cultures adapted it to their culinary practices. However, there are some common denominators. All Jollof dishes are tomato-based sauces and usually include bell peppers, onions, and scotch bonnet chillies.

A festive dish, one can expect Jollof to be served at large gatherings like birthdays and weddings. Although Jollof is a great meal all on its own, it is also eaten alongside other foods.

The term ‘Jollof’ is only used in countries where English is the official language (Sierra Leone, Liberia, Ghana, and Nigeria). In most Francophone countries (Guinea Bissau, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso, Niger, Benin, and Togo) it is called Riz au Gras (translates to ‘rice with fat’). However, in The Gambia and Senegal, it is called Benachin (translates to ‘one pot’). In Mali, Bambara-speakers refer to the dish as Zaamè (also spelt Nsamé).

Nigeria

Nigerian Jollof is typically features long-grain rice that retains its texture throughout the cooking process. Golden Sella rice is great for these purposes because it is par-boiled. This reduces the amount of starch within each grain, preventing the rice from going mushy as it cooks and maximising flavour absorption. It is also common, yet not required, to use red palm oil. The dish is often served alongside meat and dodo (fried plantains), as well as moi moi (also spelt moin moin) and coleslaw.

A speciality in Nigeria is Party Jollof. This version is cooked over an open fire using a large cast-iron pot. The firewood imparts a unique smoky flavour to the rice. Other variations include Coconut Jollof, Fisherman Jollof, Mixed Vegetables Jollof, and Jollof Rice and Beans.

Ghana

Ghanian Jollof is usually cooked using a fragrant rice, such as Thai jasmine or basmati. These rices have a stronger taste and lead to a more flavourful end product. Additionally, Jollof from this region tends to incorporate an array of spices usually not found in other Jollofs, such as nutmeg, turkey berry, anise and rosemary. When serving, Ghanian Jollof is topped with Shito (a black pepper sauce) and eaten alongside fried plantain and either meat (usually chicken) or fish (usually shrimp).

The Gambia and Senegal

Benachin is reminiscent of Thiéboudienne in its composition, where meat is laid down on a bed of rice, surrounded by a group of vegetables. However, Benachin stands out by incorporating a more substantial amount of tomato and often features chicken instead of fish.

Liberia

Creole techniques and ingredients influence the making of Liberian Jollof. For example, it may contain a mix of meats such as beef, chicken and ham. Like in Nigeria, red palm oil is commonly used.

Sources

Davidson, A. (2014). Oxford companion to food (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. https://app.ckbk.com/reference/food77337c10s001e050/jollof-rice

Egunsi Foods. (2022, December 12). Thiéboudienne: Jollof rice’s senegalese origins. https://egunsifoods.com/blogs/recipes/Thiéboudienne-jollof-rices-senegalese-origins#:~:text=Thi%C3%A9boudienne%20is%20Senegal’s%20version%20of,’fish’%20(j%C3%ABn).

Eniola, A. (2020, February 5). What you didn’t know about jollof rice. Y! Africa. https://yafri.ca/what-you-didnt-know-about-jollof/

Exploring Africa. (2023). Module twenty three activity two. Michigan State University. https://exploringafrica.matrix.msu.edu/module-twenty-three-activity-two/

Freelon, K. (2006, June 1). Thiéboudienne. Bonjour Paris. https://bonjourparis.com/archives/Thiéboudienne

Johnson, C. (2023, November 7). This is how jollof rice became an iconic West African staple. The Knot. https://www.theknot.com/content/jollof-rice#history-of-jollof-rice

Le Point Afrique. (2021, December 16). Senegal: Thiéboudiene listed as a UNESCO world heritage site! Le Point Afrique. https://www.lepoint.fr/afrique/senegal-le-thieboudiene-inscrit-au-patrimoine-mondial-de-l-unesco-15-12-2021-2457108_3826.php

McCann, J. C. (2009). Stirring the pot: A history of West African cuisine. Oxford University Press.

Osseo-Asare, F., & Baëta, B. (2015). The Ghana cookbook. Hippocrene Books.

Sloley, P. (2021, June 8). Jollof wars: Which does West Africa’s iconic rice dish best? BBC. https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20210607-jollof-wars-who-does-west-africas-iconic-rice-dish-best#:~:text=Rice%20farming%20flourished%20in%20this,sumptuous%20rice%20dish%20with%20them

Sokoh, O. (2014, November 9). Part 1: A short history of jollof rice. Kitchen Butterfly. https://www.kitchenbutterfly.com/2014/part-1-a-short-history-of-jollof-rice/

Thaim, P. (2022, August 1). What is jollof rice? Food Network. https://www.foodnetwork.com/how-to/packages/food-network-essentials/what-is-jollof-rice

The Past is a Foreign Pantry. (2010, October 7). Jollof rice. https://thepastisaforeignpantry.com/2020/10/07/jollof-rice/

UNESCO. (2021). Ceebu jën, culinary art of Senegal. https://ich.unesco.org/fr/RL/le-ceebu-jn-art-culinaire-du-sngal-01748

UNESCO. (2021). Decision of the Intergovernmental committee: 16.com 8.b.36. https://ich.unesco.org/en/Decisions/16.COM/8.b.36